How far do you live from your local town hall?

The distance might matter more than you think. A new study shows in numbers what citizens in smaller municipalities lost during Denmark’s municipal reform – and it offers new insights into the broader welfare debate.

What happens to a local community when it loses its town hall? That question has been the focus of a new study conducted by three researchers, published at a time of local elections, discussions about public sector efficiency and an ongoing debate about Denmark’s regional imbalance.

The researchers analysed the consequences of the 2007 municipal reform, when the number of municipalities was reduced from 271 to 98. In each of the newly merged municipalities, only one town hall was kept – usually in the largest town. This created a unique opportunity to study how the loss of local administration affects residents’ behaviour.

“If the expectation behind the reform was that people could live anywhere in Denmark and enjoy the same level of welfare, that has clearly proven to be a poor assumption.” Ismir Mulalic

Associate Professor

Findings show that areas without a town hall experience significant depopulation. Families with children and people of working age tend to move to areas offering better public services and shorter commutes. At the same time, property prices drop in affected areas due to weaker demand.

Local schools and healthcare services such as medical clinics also experience a reduction in capacity and staff, creating a negative spiral where fewer services lead to fewer residents – and fewer residents lead to even fewer services.

A MISTAKE TO ASSUME PEOPLE WOULD STAY

“The idea behind the reform was to centralise administrative tasks and achieve economies of scale, but it was a mistake to assume that people would stay. When the distance to schools, doctors and jobs increases, people move, and that sets off a domino effect. The reform has contributed to rural decline and increased urbanisation,” says one of the researchers behind the study, Ismir Mulalic from CBS.

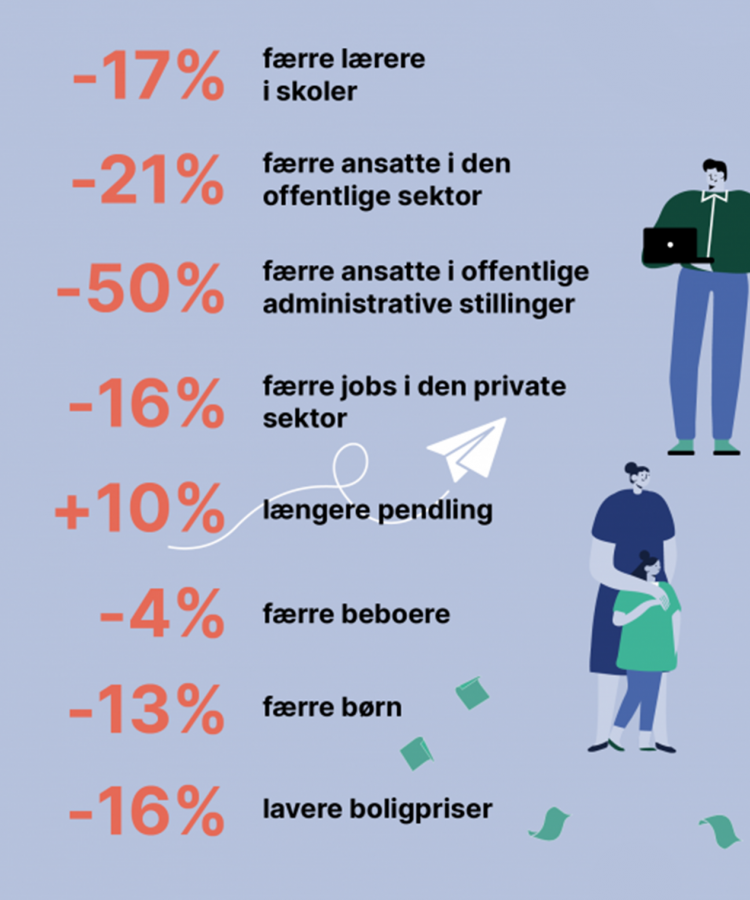

In numbers, the study shows that the reform not only halved the number of public administrative positions in the 173 municipalities that were discontinued, it also led to school closures – nearly one in five teaching positions disappeared. In addition, the reform reduced business activity in these areas: nearly one in six private sector jobs vanished within the following ten years.

Depopulation followed, and the number of residents of working age fell by 4 percent, while the number of children declined by 13 percent. For those who stayed, the distance to work increased – while the value of their homes decreased.

When newcomers did arrive, they tended to have lower education and income levels, which changed the local socio-economic profile, and this has had implications for both tax revenues and civic engagement.

UNEQUEAL WELFARE

The study shows that the reform has widened the gap between urban and rural areas. Municipalities such as Esbjerg, Aalborg, Viborg, Aarhus, Odense and Copenhagen have grown, as have their neighbouring municipalities. Meanwhile, areas such as Langeland, Lolland, Lemvig and Frederikshavn have generally lost residents.

“If the expectation behind the reform was that people could live anywhere in Denmark and enjoy the same level of welfare, that has clearly proven to be a poor assumption,” says Ismir Mulalic. As an economist specialising in urbanisation, he notes that the global trend is towards increasing urban concentration. Still, he calls for more political reflection on how the relationship between city and countryside should develop.

On the one hand, we introduced a reform that accelerated depopulation in smaller towns. On the other, we spend billions trying to bring Denmark back into balance. The relocation of public jobs alone has cost billions. It seems contradictory. So do we accept that cities will continue to grow at the expense of smaller communities? And do we really understand the mechanisms behind it?” he asks and adds:

“This discussion remains unresolved. But our research shows that removing local administration affects the housing market, the local workforce and the availability of public services.”

A CLEAR PICTURE

Together with Marie Louise Schultz-Nielsen from the Rockwool Foundation and Bence Boje-Kovacs from Aalborg University, Ismir Mulalic has analysed data from 1996 to 2015, comparing areas that lost their town hall with those that did not.

While earlier research has often focused on potential administrative gains from municipal mergers, this study examines the economic and demographic consequences for the communities that lost their municipal status and local administration.

The results, published in the Journal of Economic Geography, paint a clear picture: areas that lost their town hall and thereby their status as an administrative centre fell behind comparable areas that were not merged.

About the researcher

- Ismir Mulalic specialises in transport and urban economics

- Associate professor at the Department of Economics, CBS

- Formerly affiliated with the Technical University of Denmark and the Kraks Foundation – Institute of Urban Economics

- Read more about the researcher

Facts

Key findings in affected areas:

- 17% fewer teachers in schools

- 21% fewer public sector employees

- 50% fewer public administrative positions

- 16% fewer private sector jobs

- 10% longer commuting distances

- 4% fewer residents

- 13% fewer children

- 16% lower property prices

- The study is titled ‘The domino effect: exploring residential mobility in the aftermath of municipal mergers’ –

https://academic.oup.com/joeg/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jeg/lbaf038/8262208. - Supported by the Rockwool Foundation