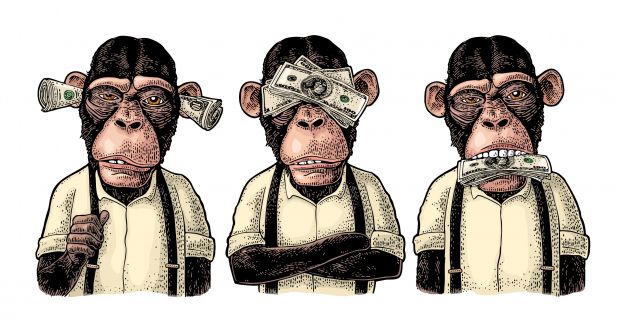

We are willing to compromise our morals for money – but there is a limit

Photo: Shutterstock

People act morally if it does not cost them any extra. If the price is too high on a personal financial level, we are more selfish and willing to compromise our moral beliefs.

This is the conclusion of a new peer-reviewed CBS study.

“We bend our morals when something is too appealing and no one is watching,” explains Luigi Butera, Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics at CBS.

In collaboration with researchers from France, he has investigated how our brains respond when we are faced with decisions that cost us economically or morally.

“We found that people act morally when it is cheap. For instance, when a small donation generates a large benefit for others. But when the monetary stakes increase, people become more selfish,” explains Luigi Butera.

24 men were monitored in an fMRI-scanner

In order to test what is at play in our minds when we make moral decisions, the researchers selected 24 men without any history of mental illness.

The men were given an amount of money and asked to make 256 investment decisions while being monitored in an fMRI-scanner.

Half of the investments would lead to a monetary payoff for the participants and the other half to a loss.

The investments that would lead to a monetary payoff for the participants were donated to a so-called ‘bad cause’. This resulted in more money for the participants but also a sense of moral loss.

However, the participants could still gain something from the investments that led to a loss of money – moral satisfaction because the investments were donated to a ‘good cause’.

The fMRI-scans of the 24 participants’ brains showed that three areas were particularly active during decision-making:

“In dilemmas involving a moral cost and a material benefit, the brain regions involved were the anterior insula and the lateral prefrontal cortex which are associated with anticipation of punishment. In dilemmas involving a moral reward and a material cost, the ventral putamen, which is associated with the anticipation and calculation of rewards, was involved,” Luigi Butera says.

We act amorally to get what we want – when no one is watching

By testing how the participants invested the money when an audience was looking, and when they were alone, the researchers made another interesting discovery:

“We found that the extent of the selfish decisions is determined by the presence of an audience: people act more morally when their actions are visible to others,” Luigi Butera says.

The need to be socially accepted by the group serves as a natural limit to how selfish we act in investments, he elaborates.

This means that we are willing to bend our personal beliefs to gain profit – as long as it does not harm others or makes us look too bad.

Altruistic or selfish?

According to Luigi Butera, every decision we make involves at least three moral concerns.

- Your personal values motivate you to act in certain ways.

- The anticipated reward – what can you gain or lose from this?

- The social motivation – whether others observe your choice or not.

The reason we as humans have a sense of moral has to do with evolution and survival.

“We want to fit in and be accepted by the group. We depend on others to survive and in order to be liked, we need to make moral decisions,” Luigi Butera says.

The fact that we make moral choices to fit in suggests that the moral choice is also a selfish choice.

“Yet the participants of the study also felt bad about doing something amoral when no one was watching. This indicates that the question of moral is not all selfish. It is really complex and we still don’t have all the answers,” Butera explains.

Provides insights into the prevention of amoral behavior

The findings of the study, published in PLOS Biology, can provide useful knowledge about how a society can discourage amoral behavior, Luigi Butera thinks:

“The brain regions associated with anticipation of punishment are active when we decide to do something morally wrong for a personal material gain. This means that a police officer saying ‘pay your taxes or go to jail’ will be more effective than one saying ‘be a good guy and pay your taxes’,” Luigi Butera explains and continues:

“Reversely, when we decide to do something morally good at a personal cost, the brain regions associated with anticipation of reward are at play. This suggests that it could be more efficient to stress the benefits of doing something good rather than the downsides of doing something bad when trying to encourage morally good behavior in people,” Luigi Butera concludes.

| "Men and women have skulls that are slightly different anatomically, so for technical and statistical reasons it is easier to conduct studies with participants of same gender," explains Luigi Butera. |

For more information please contact journalist, Ida Eriksen